When to Invest in a Fundraising Campaign Test? 3 Questions to Ask

As direct response fundraisers, we are comfortable playing the waiting game. Particularly in direct mail, we work for months to prepare the best package we can. We draft copy that inspires giving, and select imagery that pulls at the heartstrings. We evaluate ask amounts and audience selects. We produce the package, drop it in the mail … and then we wait — often for three months or more — to see if it was everything we hoped it would be.

Did our effort drive the response we hoped? Did it bring in more high-dollar gifts? Did we improve our ROI? How’s the net revenue look?

That’s a lot of time and effort spent to find something that might (or might not) work and eventually become our control package. Once we find that control, it can feel risky to make any additional changes that might degrade performance.

And so, to minimize risk, we test new ideas in small quantities, measured against a similarly sized subset of the control, in an attempt to improve performance. This makes sense.

However, this practice can rapidly turn into a test obsession in our efforts to ensure we don’t break anything as a package evolves. It’s a practice that can easily snowball, wasting time and resources on things that probably never really needed to be tested and will never “move the needle.”

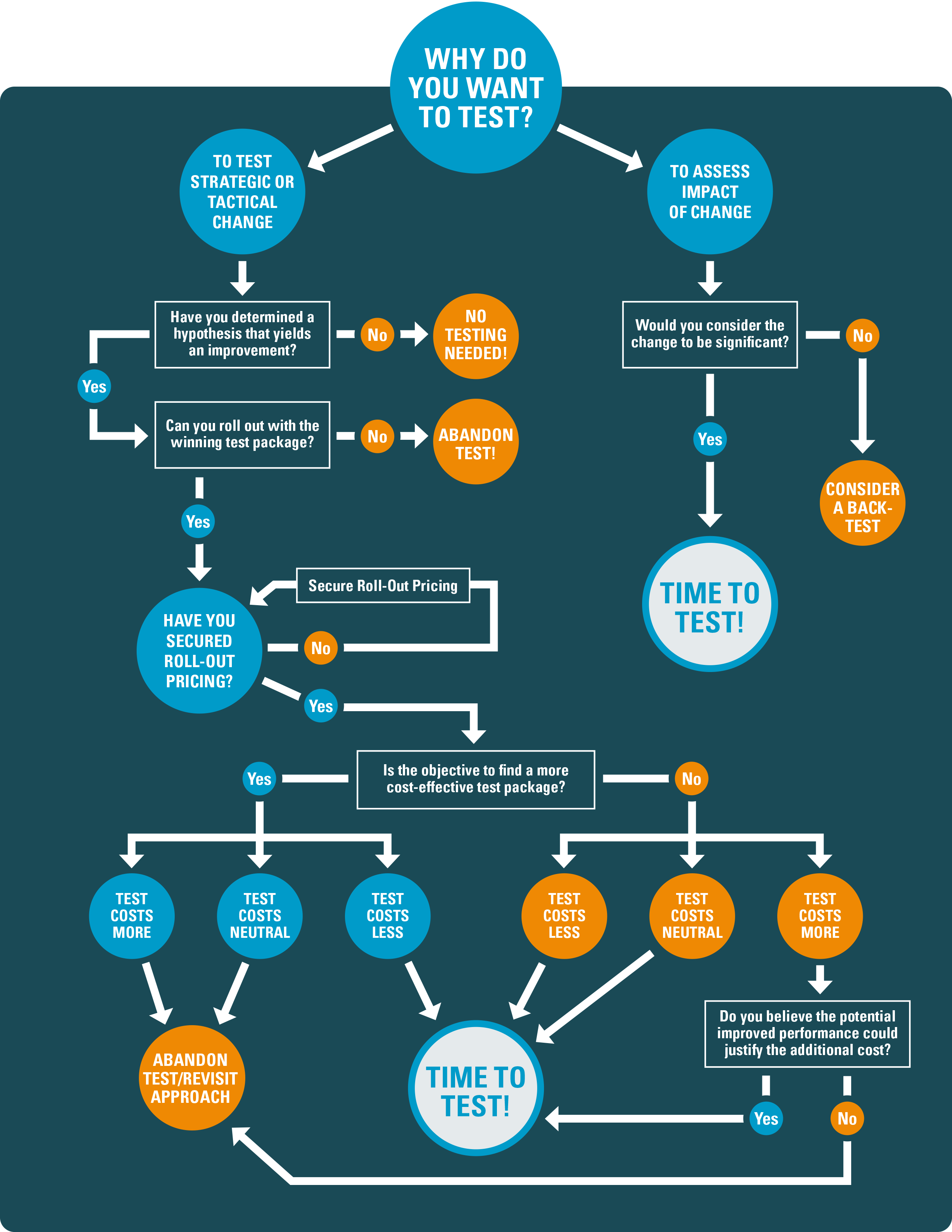

How can you know a direct response fundraising test is worth the investment? You can start by asking yourself three questions:

- Why are we testing?

- What’s my hypothesis?

- What if it wins?

The following decision tree can guide your go/no go testing process.

Why are we testing?

This may seem easy and obvious. But the response to this question can be extremely telling. The most important reason you should invest in a test is because you believe the strategic or tactical change can “move the needle” and improve performance.

Full package tests; new offers or gift arrays; or significant changes to format, cadence, message, and creative — these can be needle-movers. (Logo and brand modifications are also needle-moving changes that absolutely should be tested, but sometimes cannot be avoided, regardless of the test results.)

Changing the word “good” to “great” in copy? Not a needle-mover. Changing a blue line to red line in your design? Not a needle-mover. Just make these changes. They are low risk, and often result in neutral performance between a test and control package.

If in doubt, and the change (and therefore risk) is acceptably small, it may be worth considering something called a back test. A back test is set up very similarly to a typical test, except the test package is sent to the majority of the audience with the control being mailed only to a small panel. This allows you to still secure informative data points while moving ahead more quickly, in the unlikely event these changes may have more impact than you think.

Gathering these testing data points (both good and bad) are invaluable to inform future decisions, roll-out plans, and budget projections.

What’s your hypothesis?

All good tests need a hypothesis. This relates back to the belief that the test will improve performance. Some examples:

- We believe adding a teaser on the outer envelope will drive more people inside the package, boosting the likelihood that more donors will respond. We expect this test to improve response rate — with little to no impact on average gift.

- We believe if we serve a more aggressive ask string in acquisition that we can increase the value of first gifts. We expect this test will lower response rate, but increase average gift from those who do respond.

Identifying your hypothesis in advance of testing can help ensure that the test ladders back to a program or campaign objective and has a direct correlation with a program metric. It also identifies the metrics against which you will determine success (or failure).

If your test does not have a hypothesis that can directly impact donor behavior, it’s probably not worth testing.

What if it wins?

This is an important one.

Obviously, testing a package you aren’t willing — or can’t afford — to mail in the future is wasted effort.

Typically, testing is executed in a small subset of an audience to reduce risk. As a result, cost per thousand (CPM) rates are comparatively high, depending on the nature of the test. Therefore, it’s important to understand what are called roll-out costs. Roll-out costs are the estimated costs for mailing the test package to the full audience if it were to win. Roll-out costs, not test costs, should be compared to the costs of the control.

- If the cost of the test is less than that of the control — great! If it outperforms the control, you’ll have a new control. (If the test was to reduce costs, it need only match the performance of the control.)

- If the cost of the test is the same as that of the control, then ask yourself did the test results meet the objective? If yes, then great again!

- If the cost of the test is more than that of the control, then calculate the boost in performance, and determine if it was sufficient to offset the additional cost and still generate the desired outcome.

If you can identify why you are testing, and you have created a hypothesis of how that test is going to better your program, and you have a clear plan for rolling it out to a larger audience if it wins, then you've got yourself a worthy test.

Here’s hoping it’s a winner!